About

Jennifer Cecere was born in Richmond, Indiana, and lives in New York City.

She has spent over 40 years expanding and experimenting with the mapping qualities of needlework.

Her work has been exhibited in Central Park, The Guggenheim Museum, Pratt Institute Sculpture Park, Socrates Sculpture Park, MoMA/ PS1, The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Museum, The Addison Gallery of American Art, Mamco, Geneva Switzerland, Le Consortium, Dijon, France, The Hudson River Museum, The Herbert F. Johnson Museum, The Burchfield Center. Public Art Commissions include the New York City Department of Transportation, The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA), and the City of Newport Beach, California.

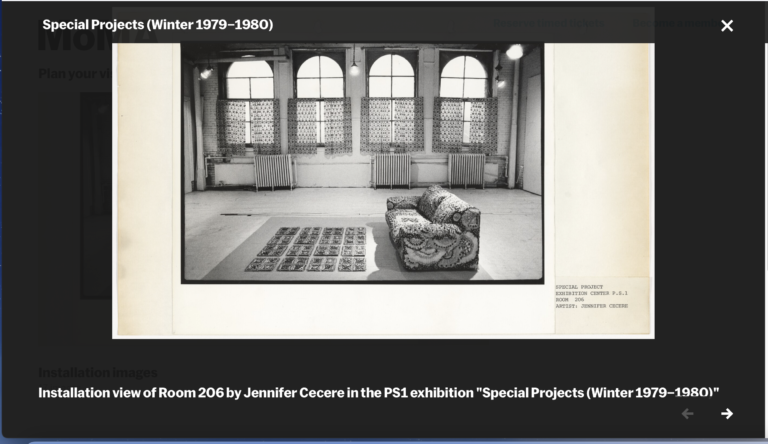

“In My Room” 1979 t at Moma/PS1, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/4146 was the first of many installations. Given an old classroom to transform she created a domestic interior of lace and paint. “In My Room” was just the first of many installations of “rooms”.

“Jennifer Cecere has transformed one of the forbidding classrooms into a gaudy intimate place she names ‘In My Room’. No sternly minimal intellectual pretensions there. Just too much texture, color, humor, and a surfeit of marzipan genutlichkeit. The rug is a pink square painted on the floor, the overstuffed sofa is covered in an orgy of sequins and buttons and beads, and plastic squiggles seemingly laid on with a cake decorator. Ditto the curtains, and the tablecloths and the wall hangings and even the antimacassars everywhere.” – Amei Wallach, Everyone Wants to get into P.S.1., Newsday, 1980.

Recent shows include Pattern, Crime & Decoration, 2018-19, Le Consortium, Dijon, France, and MAMCO, Geneva Switzerland 2019, curated by Franck Gautherot and Seungduk Kim with Lionel Bovier, MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland.

“Pattern, Crime & Decoration features the groundbreaking, artist-led American art movement Pattern & Decoration, which started in the mid-1970s and lasted until the mid-1980s. Often viewed as the last organized art movement of the 20th century, it chronologically straddles the end of modernism and the beginning of postmodernism, through its rejection of the rigid tenets of formalism and its embrace of decorative motifs and non-Western visual forms. Strongly grounded in feminism, it included many women artists and sought to highlight some kinds of arts and crafts often dismissed as belonging to the domestic or decorative sphere such as tapestry, quilting, wallpaper or embroidery.” Franck Gautherot and Seungkduk Kim